What I Learned from My Parents, Elders and Peers about the Gift of Community

Two – Vulnerability and Belonging

My previous blog contains the 1960s story of Mwami Semei of Kiwafu Village, Entebbe, Uganda, and how Mwaami Semei stumbled into belonging and community only after the tragic event of his wife’s death. Mwaami Semei’s story is in fact a parabolic reflection of why each one of us and all of us together need to live and work together in community. We can find community in many places and situations: in our nuclear families, in our extended families, in our clans, in our churches, in our clubs, in our villages, in our towns, in our Districts, in our Provinces, in our Kingdoms, in our nations (like Uganda), in our nation-groupings (like the East African Community), and so forth and so forth. Life is about building, nurturing and living in these relationships.

Unfortunately, many people may not be aware of these relationships and their value, let alone how to grow and nurture the relationships. Worse still, many more others are very much like Mwami Semei and his wife. They are afraid that living in true communion and relationship with others will expose their weaknesses and vulnerabilities and compromise their ability to pursue their own self interests. This is a condition that especially afflicts those that have or seek to have any form of authority over others, whether this authority is formalised or unformalised.

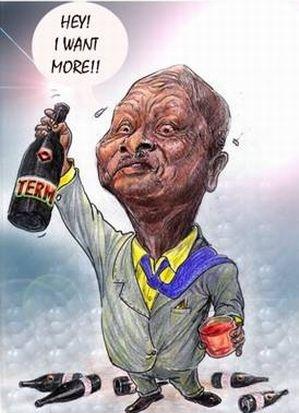

The schoolyard bully, … the footballer who does not mind breaking someone else’s leg to win the game, … the President who will do anything to stay in power for all his life, … the Police Commander who orders his fellow citizens to be shot for walking to work instead of using other means of transport, … the judge who unjustly sides with the rich and powerful and denies the poor their rights, … the professor who awards unearned grades for sexual favours, … the millionaire who bribes the land officer to take a poor neighbour’s land, … ; the list can go on and on. Each one of us could be any of these people. There is a way in which we have all bought into the modern capitalist and technology-driven culture and education system. We think that we must rise to the top, and we make this the primary purpose of life! We must be winners, even if this involves the destructive philosophy of ‘either I/we win or they lose!’. The world comes to an end when we are losers. People even kill others in order not to be losers.

In order to live this kind of life, one must deny their humanity. They must deny that they are mere mortals with weaknesses and vulnerabilities. And they must also deny the humanity, entitlements and rights of others. To deny human weakness and vulnerability of self and to dehumanize others is to enter a world of loneliness, and yet go to on pretending that one has it all and is not lonely. This is the core of what Conrad called “The Heart of Darkness”. It is a wounded heart that would want to prove that it has no love. It seeks and craves to be admired. It emphasizes competency and efficiency (with slogans like “We have brought this country peace and economic development.”) and power (often with militaristic responses to everything imaginable). However, neither the self-anointed efficiency nor the expropriated power flows from what my friend Muniini Mulera once alluded to as “The Heart of Goodness”. It is only possible to use competency, efficiency and power to bring people together if those attributes flow from “The Heart of Goodness”. Whether participating in our family lives or in our nation’s affairs our labours will find genuine reward and bear fruit only if they flow from “the Heart of Goodness”.

Some time in 1971, Daniel Kyanda who had just become the first Ugandan Headmaster of King’s College Budo was speaking privately to a group of OBs (Old Budonians) who had gone to the school for the opening of the new Australia House buildings. Amin had just overthrown Milton Obote and declared himself the President of Uganda. Kyanda made a prophetic comment about Idi Amin and the country’s leadership in general. He said, “My problem with our new leader is that, like Obote, he demands respect; he does not command respect. … I wonder where all this will end up.”

Uganda is a tragic example of how a terribly broken place the world is. In its fifty-plus years of “Independence”, the country has been governed only through fiat and oppression. Along the way it has endured a number of internal and external wars. Impunity abounds: thus the pervasive situation where those in authority do whatever they please without any fear that they can be subjected to any moral, constitutional or legal sanctions.

Inequalities abound, with a few who have too much and the very many that have too little. The poor are crying out for food and love. They wonder whether what former President Milton Obote used to say in the 1960s, “ONE NATION, ONE PEOPLE”, was ever or will ever be a reality. They long for their leaders to say, “You, the people of Uganda, are important, you have value.” Such a statement is long overdue from Uganda’s leaders. It can be made in a combination of different ways, including attitudinal changes, policy changes, resource allocation, and so forth.

Religious leaders give President Museveni a gift (a captioned portrait of himself) to congratulate him for signing the anti-gays bill into law.

Short of such a statement, the people of Uganda wonder what the President, the First Lady, the First Children, the First In-Laws and their close friends mean when they continually declare, “I am a born-again Christian.” God is a God peace, joy, love and hope. God does not want Ugandans to be a nation of people that continually lie to each other, people who beat up and otherwise brutalize each other at the least provocation, and people who casually kill each other in sacrifice, hatred and revenge rituals and orgies. Wrapping oneself in “born again Christian” garb is facilitated by the ways in which most religious leaders and common pastors have been co-opted into the dictator’s patronage networks. It has also become a convenient way for people, especially leaders, that are deep in immorality and illegality to pretend that nothing is wrong. It is a way for such people to, as it were, bury their heads in the sand and imagine that they are immortals who are not vulnerable to the twists and turns of this world.

Like Mwaami Semei before the death of his wife, our leaders are devoid of any sense of vulnerability. To be vulnerable is to recognise we are mere mortals: our time in this world is finite; and anything, both good or bad, that can happen to any one of us at any time. It is to realize that for the finite time that we each have in this world we need each other. We need each other in our families, in our social grouping, and in our political and national groupings.

What attributes, then, should we expect of our leaders that would make them effective builders of and co-participants in community in their nation? Our leaders need to stop doing things simply to prove that they are powerful, and that they are not vulnerable like the rest of their compatriots. They should stop trying to imprint messages on others simply to improve themselves. They should stop hiding and running away from the spiritual centre of humanity – which is that we are all born equal; we all come into this world with nothing and leave it with nothing; and any future beyond what we experience on this Earth has to be in the hands of Someone who is greater than any human being or animal that has ever lived in this world. Our leaders should let their everything (motives, plans, actions, etc) flow from the spiritual centre of their humanity. After admitting their vulnerability, our leaders must open themselves up. Opening up oneself means welcoming the other person (warts and all), listening to the other person, hearing what the other person has to say, hearing and feeling the other person’s pain, and seeing and appreciating and embracing the other person’s gifts and talents. Our leaders need to understand that becoming vulnerable means that they too can be hurt, and that there will be costs and pain. Only then can they enter into and play a role in a world of meaningful relationships and community.