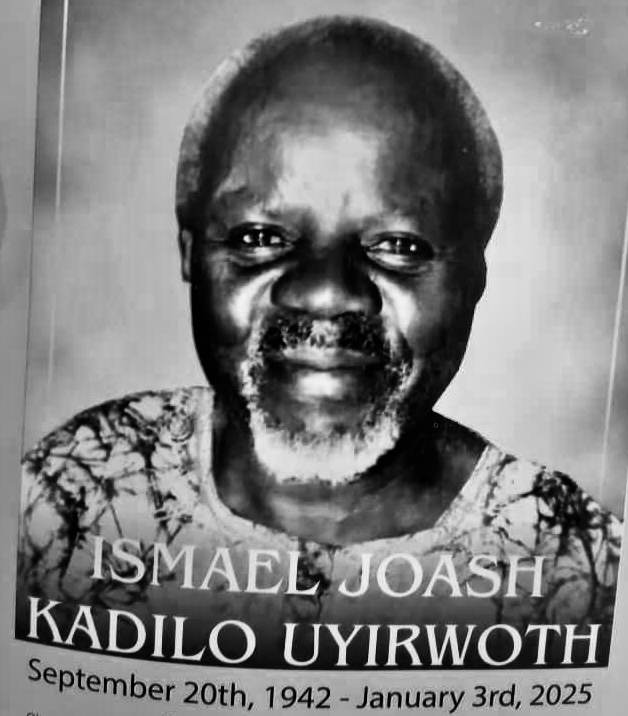

Ismael Joash Kadilo Uyirwoth may not have been well known to most present-day Ugandans. However, Uyirwoth, the ninth headmaster of King’s College, Budo (1975-1979), who died at the age of 82 on January 5, deserves a place of honour among the most impactful post-independence citizens of Uganda. Few people were suddenly assigned a task as challenging and thankless as he was. Few people were as misrepresented and misunderstood as he was. But few people possessed a will to succeed against the odds like he did.

Uyirwoth, the chief inspector of geography in the ministry of education, became headmaster of Budo by default. By 1975, Daniel Musisi Kyanda, the headmaster since 1971, had reached a personal mental and physical breaking point. He wanted out of Budo and informed the board of governors and the ministry of education that he was calling it quits.

When the board of governors failed to find a “suitable” replacement for six weeks, the permanent secretary and the chief education officer informed Uyirwoth that they wanted him to become the headmaster of Budo. He declined the offer, with the explanation that he was neither an old Budonian nor a Muganda, and he was happy in his job at the ministry.

Uyirwoth, who was travelling to Nairobi for a conference, was given two weeks to consider the matter. Upon his return, he was summoned to the office of the chief education officer. On his way up the staircase, he met Kyanda going down. The latter told him: “Congratulations! You are the next headmaster of Budo.” Kyanda continued his journey down the stairs. It was a Tuesday. Uyirwoth was instructed to assume office on Thursday of the same week.

In short, Uyirwoth was sent to Budo as a "tetulina kya kukola" (we have no option) measure. Sadly, Ugandans, with our love of guessing and not bothering with the truth, decided that Uyirwoth was sent to Budo by Idi Amin. Being an Alur from West Nile was enough evidence to convict him without interrogation of the facts. His baptismal name, which many assumed to be Islamic, his ethnicity, and his appointment during the rule of Gen. Amin were enough evidence to deny him a warm Christian Budo welcome. This folly of assumption, driven by ignorance and disinterest in establishing the facts, conspired to make his stewardship of the great school more difficult than the deteriorating national landscape had imposed.

By 1975, Budo was falling apart like everything else in the land. Uyirwoth, whose Alur name means “believe (or trust) in the Lord”, surrendered all to God and did his best to save Budo. He used unorthodox measures, including occasional physical persuasion, to communicate with wayward students. A drunken student reportedly punched him in the face. A student detention room, which served as a prison of sorts, was in place by 1976. Like the rest of the country, Budo was in a crisis. But the indefatigable headmaster soldiered on.

The Uganda-Tanzania war of 1978/79 found Uyirwoth at Budo. Being a West Niler, he was an automatic target of the invading Tanzanian army and their accompanying Ugandan “freedom fighters.” He received death threats, but he stayed with his students to ensure their safety. Finally, he received an order to hand over to a new headmaster “within 24 hours.” Uyirwoth defied the order, and took ten days to produce what Gordon McGregor, the Budo historian, described as a “masterly summing up report of his time at Budo.”

In that report, Uyirwoth made important recommendations that Professor McGregor shared with us during a fundraising dinner for Budo in Meadowlands, New Jersey, USA on May 28, 2005. “There is no future for Budo until Budo’s staff can learn to behave themselves,” McGregor quoted Uyirwoth. “He had had to put up with a great deal of indiscipline and drunkenness by staff. And I think there is also no future for Budo unless it can get out of its regressive and negative conservatism and have a considered policy of progressive conservatism. And that means, yes, conserving the best of your past, but also be willing to change.”

Uyirwoth’s crisis appointment and experience could have been prevented in 1970, the year that Ian Cameron Robinson, Budo’s last expatriate headmaster ended his outstanding stewardship of the school. When Robinson notified the government of his intention to retire at the end of 1969, President Milton Obote prevailed on him to stay on for another year. This gave the school’s board of governors plenty of breathing space to headhunt a qualified, experienced and interested successor to Robinson.

This ideal was sabotaged by two factors. First, Obote’s insistence on rapid Africanization of academic institution leadership ruled out succession by one of the expatriate teachers at Budo. Yet several British and an Australian on staff would have made superb headmasters. Their careers after Budo affirm my belief. Two examples: Following his departure from Budo in 1972, Neil Bonnell, an excellent teacher of English, taught at his alma mater, Trinity Grammar School in New South Wales, Australia, for twelve years. He was deputy headmaster for eight of those years. He then served as Principal of the Scots PGC College in Warwick, Queensland, Australia for ten years.

When Roger Gillard, our outstanding history teacher, returned to England, he continued teaching, became headmaster of Milton Abbey School in Dorset, Southwest England, and capped his career as Headmaster of Malvern College Junior School, Hillstone in Worcestershire, West Midlands, England for fifteen years.

Second, the board of governors and the top-level leaders of Namirembe Diocese of the Church of Uganda operated within an insular bubble. The appointment of Kyanda as Robinson’s successor was a very ill-considered measure. The 30-year-old gentleman, who was working at the Pan African Fellowship of Evangelical Students in Nairobi, was neither interested in the job nor qualified or experienced for it. In his own words many years later, Kyanda would not have applied for the job had it been advertised.

Yet there were several qualified educationists that would have been excellent considerations for appointment. These included Besweri Mawata, District Education Officer, Ankole; D. N. Okunga, Director, Centre for Continuing Education, Makerere University College; Y. Y. Okot, Inspector of Schools, Ministry of Education; and Zabuloni Kabaza, previous Headmaster of Kigezi High School, who had recently become Headmaster of Kyambogo College School. Was this mistake due to the regressive and negative conservatism that Uyirwoth and McGregor talked about?

There was an argument, still held by some today, that the headmaster of Budo had to be an old Budonian. In my view this should have been very low on the list of criteria. Leadership ability, solid experience, strong Christian faith, excellent academic credentials, and an agreeable character (affability, excellent public relations skills, and good personal morals) should have been the essential qualities sought.

One notes that Budo’s seven expatriate headmasters were not Old Budonians. To a man, they all did excellent work in building a school that became one of the best in Africa during its first 65 years or so. Notwithstanding the severe hardship and challenges he faced, Uyirwoth tried to do likewise for his students. And succeeded. Most of his students turned out very well. They became highly accomplished professionals in Uganda and abroad.

Uyirwoth saved Budo. That should be his epitaph.

© Muniini K. Mulera