The purpose of this Prologue is to lay out the central message of the series of articles. In this way, the Prologue is intended to highlight for the reader what the author considers to be the fundamentally important concerns that need to be examined and addressed.

Ever since Independence was attained some 60 years ago, the principal occupation of each of Uganda’s successive governments has been to muster and use as much military, paramilitary, Mafiosi, warlord and vigilante muscle as possible to survive, to stay in power, to reward themselves and their supporters, and to simply cope in a culture of pervasive violence.

There was no time wasted after Uganda’s Independence before major fissures were exposed within and between the main political groups, parties, factions and cabals that the British colonials entrusted the newly independent country to. It was not just differences in policy choices and emphases and leadership style between the official government side and the official opposition, as characterised in many parliamentary systems of government. In hindsight, one wishes it had been just that. Instead, the additional differences were deeper and more lethal than that.

There were tectonic fissures between the two political parties, namely Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) and Kabaka Yekka (KY), which formed the coalition government that led Uganda into Independence. Then there were additional fissures within each of the two coalition parties, namely UPC and KY. The Democratic Party (DP), which as the official opposition would have been expected to provide checks and balances on the official government, was torn apart by intra-party conflicts and personal struggles for its control, as well as by attacks from the coalition government and from each of the UPC and KY individually.

For a brief period, before UPC and KY turned on each other, the main objective of the coalition Government was to completely lacerate and get rid of the Opposition. For example, opposition members (from DP) were continuously insulted and vilified, and they were denied standard privileges such as an official residence for the Leader of the Opposition as well as allowances for travel, residence, purchase of cars, and others. The UPC dominated Government also bribed DP members, as well as KY members, to switch parties using offers of positions and jobs, land, houses, cars and cash.

By 1964, less than two years into Independence, the relative tranquility and the sense of a bright hope for the future that had enveloped Uganda at the dawn of Independence had disappeared. It gave way to violent conflict, including state, para-state and factional terrorism that progressively escalated and completely engulfed beautiful Uganda.

By the 1970s, the country was under the rule of a coup-installed military dictator. It became a type of a hell-on-earth for most of its residents, and also a pariah or outcast nation in the international community. After the military government was overthrown at the end of the 1970s, the country was engulfed by instability and a five-years civil war in which a cabal of young, mainly former adherents of UPC from South-West Uganda fought to stop the older 1960s UPC leadership from re-establishing themselves in power.

The younger upstarts won the civil war and formed a Government that was dominated by people from Ankole’s Bahima caste. The new Government spent about a decade pursuing a scorched earth military campaign in the Northern part of the Uganda on the pretext that they were fighting “terrorists”. The so called “terrorists” were led by two Christian religious fanatics, first Alice Lakwena and then her nephew Joseph Kony.

Neither Lakwena nor Kony nor their followers had anything to do with the Afghanistan-based Saudi, Pakistani, Yemeni who had declared an Islamic holy war and carried out some vicious attack against the US and its Western allies. Yet, the Ugandan regime used the pretext of “fighting terrorists” to whitewash atrocities committed against innocent citizens, to win the admiration and support of Western rulers, and to paint themselves into the image of a strategic bulwark against international terrorism in East and Central Africa.

Financial and military aid have flowed freely into Uganda from the Western governments and bilateral organisations, while the latter governments and agencies have turned a blind eye to one of the most cruel and human rights-violating dictatorships of the twenty-first century.

The focal point of the inquiries in Uganda at 60 – Poisoned Eden is two-pronged:

- To explain how the head-start in development that Uganda had on many other developing countries and the past tranquility of living in a growing and prosperous economy, a healthy environment, a relatively healthy and educated population and a harmonious society were supplanted by all-encompassing bad governance and state and communal violence that has hallmarks of state and state-sponsored terrorism.

- To suggest a promising and proactive strategy for mitigation of, prevention of, and recovery from the type of bad governance, deadly violence and terrorism that has afflicted and stymied the development of Uganda, and also of other countries.

Why do I consider it important to make this analysis at this time? The reasons are both personal and professional. I believe that they soundly resonate with concerns that many Ugandans and non-Ugandans have about the current and future status of the country.

Starting with the personal, for close to fifty years, I have lived outside of Uganda because I did not think that I had what it takes to thrive, let alone survive, in the culture of misrule and violence that I experienced in my childhood, youth and young adult days in Uganda; a culture that has continued to this day. I would like Uganda to be a place that I and my family could safely return to. I would also like to be able to tell people that I meet in other countries that I was born in Uganda without those people, even children, writing me off with typically derisive responses like: You come from Idi Amin’s country? ….. Are you from the same area as Joseph Kony? ….. Are you Museveni’s friend? …..

From the professional point of view, I believe that it is not impossible to recapture, recover, rehabilitate and restore Uganda to the state that our parents dreamed of and wished for their children at Independence. For almost forty of the fifty years since I left, I have lived and worked in South, South-East and East Asia. While working in Asia, I have also travelled and worked on all of the remaining continents, except Antarctica. During that time, I have been tasked to work with respective Governments, private sectors and civil societies in various countries to hone their capacities in formulating and implementing economic policies (my professional line of work) that promote good governance, build peace and reduce poverty.

Colleagues in some of these countries have often thrown the following challenge at me: “Why”, they ask, “have you never done the same work in your native country (Uganda) as you have done with us?” This is a very serious challenge because some of my colleagues remind me that their countries borrowed the original approaches, policies, plans, programmes and procedures to the development of their countries from Uganda in the 1960s.

Uganda at 60 – Poisoned Eden is, in more than one way, a response to this challenge. That is, I would like to share with my compatriots the lessons that I have learned from my experience about the relationship between good governance and non-violence and socio-economic development. Conversely, I would like to share with my compatriots the lessons that I have learned from my experience about the relationship between bad governance and violence and socio-economic under-development.

Uganda at 60 – Poisoned Eden begins with a bi-cameral parabolic illumination of a character from fiction and a character from Uganda’s politics. The fictional character and the real Ugandan politician characters are afflicted with the same fallacy of having dreams and setting goals and target that are plainly wrong, are misconstrued and are oblivious to reality.

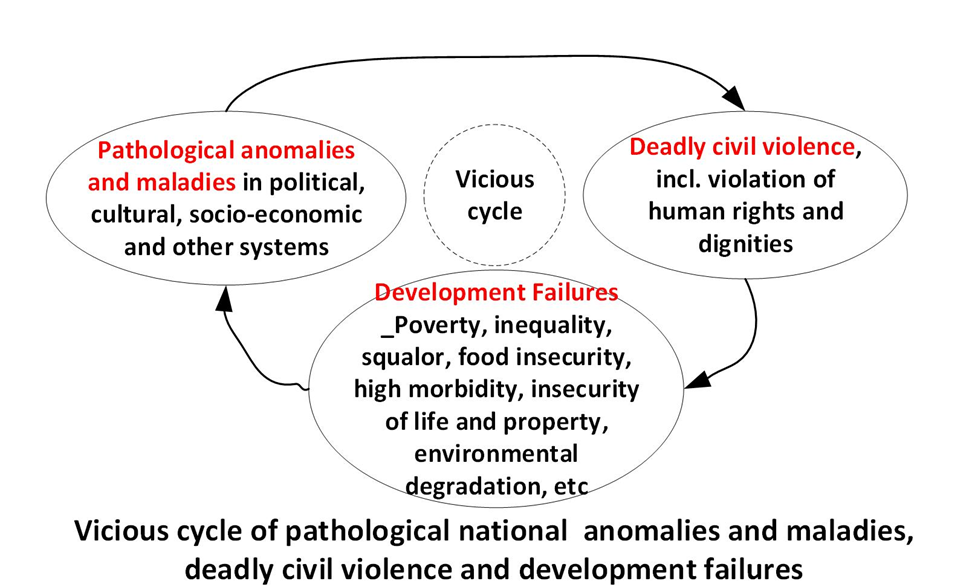

Subsequent sections of the series illustrate how this fallacy of wrong dreams and goals has been at the root of Uganda’s 60-years of turning and turning in a vicious cycle of:

- Pathological (or deathly sick) anomalies and maladies in the political, cultural, social, environmental and other systems and practices of the country.

- Deadly violent conflict, including abuses of human rights and dignities, that have permeated all manner of time and space of Uganda’s existence.

- Development failures, as exhibited in the pervasive poverty, inequality, squalor, food insecurity, high morbidity, insecurity of life and property, and other indicators of failed development in Uganda.

The topics and subject matter areas that are covered in Uganda at 60 – Poisoned Eden include:

- What Uganda was like and what the expectations of the country were before it descended into the abyss of deadly violence that has now lasted some 60 years.

- The false start to Independence during which many of the seeds of the culture of bad governance and violence were sown, sprouted and became rooted.

- The ways in which the culture of bad governance and violence has taken an iron-grip on the country.

- Examination of some of the most common explanation that have been advanced, especially by Ugandans, as to how “this” (meaning bad governance and violence) could have happened in a place like Uganda.

- Examination of the type of initiatives and measures that need to be taken to promote good governance, mitigate and eschew violence, and put Uganda back on the road to sustainable development.

Suggestions are made for ways in which Uganda can be able to free itself from the vicious cycle. The suggestions are divided into respective four categories and include the following:

Long-term multi-cultural, multi-disciplinary, multi-sectoral and non-militaristic view

- Giving weight to institutional mechanisms and discourses that extend beyond the next elections and the term in office of political leaders that are presently in power.

- Recognising that the country is made up of people with different geographical, historical, religious, linguistic and other features and traditions.

- Recognising that development is multi-disciplinary and multi-sectoral, and there is a need to have coordination mechanisms among the different disciplines and sectors.

- Prioritising the implementation of realistic and rigorous opportunity-cost analyses of military options vis-à-vis equivalent expenditure on non-military options. This is of critical importance because, ever since Independence, the military has played the most prominent role in the political and socio-economic discourse and development (or underdevelopment, as the case may be) of Uganda. The options should include the constitutionally sanctioned abolition of the military in all its forms from Uganda.

Governance, democratisation and administration

- Paying attention to meaningful devolution of power from the centre to the grassroots, and building institutions that are open to criticism, to hearing ‘bad news’ about themselves, and are self-correcting.

- Prioritising the maintenance of public order and prevention of social turbulence.

- Ensuring that internal security forces are well funded, apolitical and give preference to non-military solutions.

- Foregoing polarising political rhetoric.

Socio-Economic Development

- Deliberately framing development policies that meet people’s common aspirations – for people to feel good about their lives, the circumstances in which they live, and future prospects for themselves and their children. (Including a look backwards to the noble causes of "eradication of poverty, disease and ignorance" in independent Uganda’s first development plan).

- Prioritising the meeting of the needs and aspirations of fighting-age young people.

- Framing development policies that seek a middle path between capitalism’s efficiency and socialism’s egalitarian, even if stultifying precepts.

- Facilitating the private sector (multinational corporation, businesses and business organisations) to play a more active role in supporting successful development policies.

- Formulating and implementing development policies within the framework of sound macro-policy analysis. It is important to have a reality check on:

From the above eighteen suggestions the following four may be the most critical and catalytical to the recovery, rehabilitation, and restoration of the concept of Uganda as a nation:

- Constitutionally sanctioned abolition of the military in all its forms from Uganda.

- Meaningful devolution of power from the centre to the grassroots and building respective institutions at all levels of governance that are open to criticism, are open to hearing ‘bad news’ about themselves, and are self-correcting.

- Prioritising the meeting of the needs and aspirations of fighting-age young people.

- Preparing young people to enter a diverse labor force that requires various levels of the artistic appreciation and scientific and technological sophistication.

© Bbuye Lya Mukanga