Twenty years from now, my grandchildren will read with deep fascination a spell-binding account of a defining presidential election in which two former close comrades fought each other. They will read that the two men had enjoyed a long partnership leading a heroic struggle for freedom. They had been among the founders of the liberated nation, their signatures on the documents that would become the permanent repository of their shared hopes and dreams.

Ardently attached to their country, the two men had lived happily together in Europe for a few years, their bond solidified by the distance from home. Their country had become free after years of war. The older man had finally become president. The younger man had become his deputy and one of the most powerful and influential people in the land.

To outsiders, the two men were very close and united in purpose and deed. However, to those who cared to look deeper, no two men could have been more different.

The blunt-spoken president laboured with a perpetual chip on his shoulder, probably accounting for his attempt to adopt imperial rule. His love of speech adorned with riddles often yielded to explosive temper that sent chills down the spines of his listeners.

His deputy, on the other hand, had so tamed his emotions that he never appeared to be rattled by the most scurrilous attacks and allegations of scandal. Everything he did and said was a result of careful thought and planning, his legal mind a powerful asset in the battle ahead. He was a man clearly in the queue to lead his country.

Yet underneath that contemplative layer lurked a bite that the president would discover too late. The younger man's underground preparations to take power at the next election had been so thorough that, upon discovering the fact, the rest of the establishment appeared too shell-shocked to mount an effective push back.

It did not help that the president's party had been rent apart by deep factionalism. Whereas the country was dealing with serious threats of terrorism, foreign wars and economic uncertainty, the election was a realignment of forces that could not have been imagined a few years earlier.

The campaign was bitter, awash with slander, rumours, mutual abuse, scheming and political marriages of convenience. The result would later be viewed as the country's second revolution. After reading the final page, my grandchildren will return to the opening line of the great book: "They could write like angels and scheme like demons."

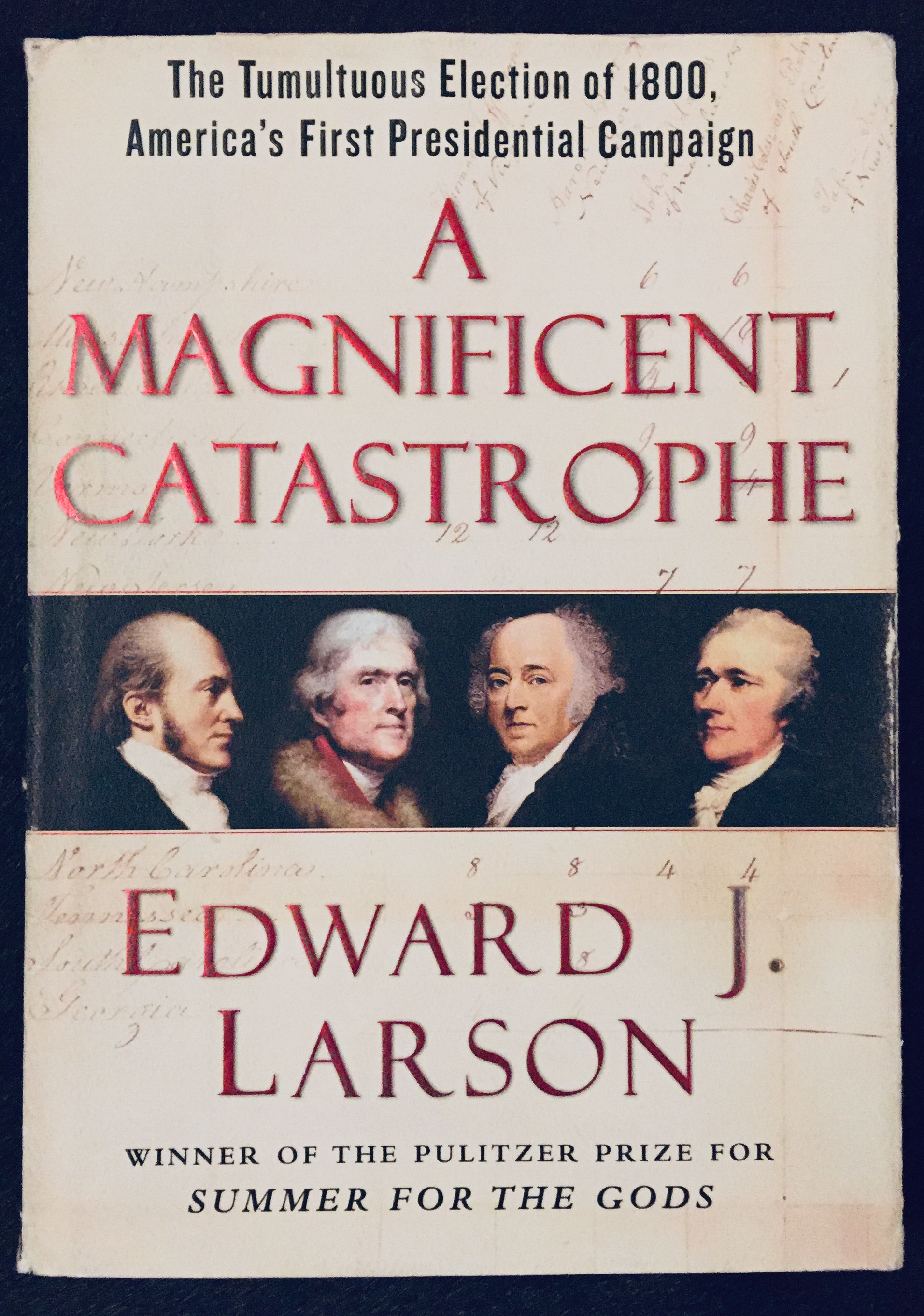

The book, A Magnificent Catastrophe by Edward J. Larson, is an excellent account of the American presidential election of 1800 in which vice president Thomas Jefferson defeated President John Adams.

It is a story of the contest between those who sought the retention of an imperial presidency and those who fought for a democracy of the masses. In the end, those who sought change triumphed, ever so narrowly, over those who wanted "no change".

Though full of fascinating parallels with the Ugandan political election of 2016, the American election of 1800 was different in one fundamental aspect: there was rule of law. The vice president of the young republic was able to challenge the incumbent president on a level political ground, assured of his rights by the rule of law. The citizens of the young United States of America were free to choose their next leader.

The Adams-Jefferson contest of 1800 was tame compared to what we witnessed in Uganda in 2016. The Ugandan episode was tyranny in the hands of a president and a few of his armed men who had already hijacked the state and had completely discarded pretense of the rule of law in order to hold onto power.

Nothing new of course, for such tyranny had already been visited upon Dr. Kizza Besigye, who had contested presidential elections in 2001, 2006 and 2011. However, the tyranny of 2016 elections made the state’s earlier efforts look like a dress rehearsal.

This time, President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni's main challenger was a former de-facto vice-president and, arguably, the closest political partner he had had for most of his rule. Contrary to the dismissive declarations of the president's spin-doctors and many opposition activists, Amama Mbabazi posed the gravest threat to the president's re-election in 2016. The NRM was in disarray largely because it had become a battleground for control by the two men.

The massive countrywide deployment of militarised police, so-called "crime preventers" and various militias loyal to Mr. Museveni indicated that the Mbabazi challenge was more formidable than anything we had seen before.

The massive rally that greeted Mbabazi in Mbale caused such panic that police banned further rallies by Mbabazi. The highly partisan Uganda Electoral Commission postponed presidential nominations for a month, presumably to give Museveni an opportunity to smoke out Mbabazi’s loyalists.

In the words of a friend who had his ear to the ground, the Museveni court had "never had to deal with such a penetrative insider as an opponent and they no longer knew who was with or against them".

Interestingly, with Museveni and his machine focused on Mbabazi, they took their gaze off Besigye. The latter quickly seized the moment and garnered huge rallies that suggested that his popularity remained undiminished. By “election day”, the Besigye supporters were feeling very confident of victory.

As it turned out, Museveni, with the assistance Gen. Kale Kayihura, his Inspector General of Police, routed his opponents and retained the presidency. Not that he won the election. We may never know who did. However, with a combination of brute force and creative vote tallying, Museveni was declared the winner. The country’s hopes of democratization were dashed once again. It was another magnificent catastrophe.