When I accepted an appointment as a resident in Paediatrics at the University of Calgary, Alberta in 1981, I had no idea what the place and the province looked like.

I imagined a flatland with endless wheat fields and, perhaps, a glimpse of the mountains in the far distance from where we would be living.

Dr. Robert H. A. Haslam

Dr. Robert H. A. Haslam Rocky Mountains, Alberta

Rocky Mountains, Alberta Male Grizzly Bear

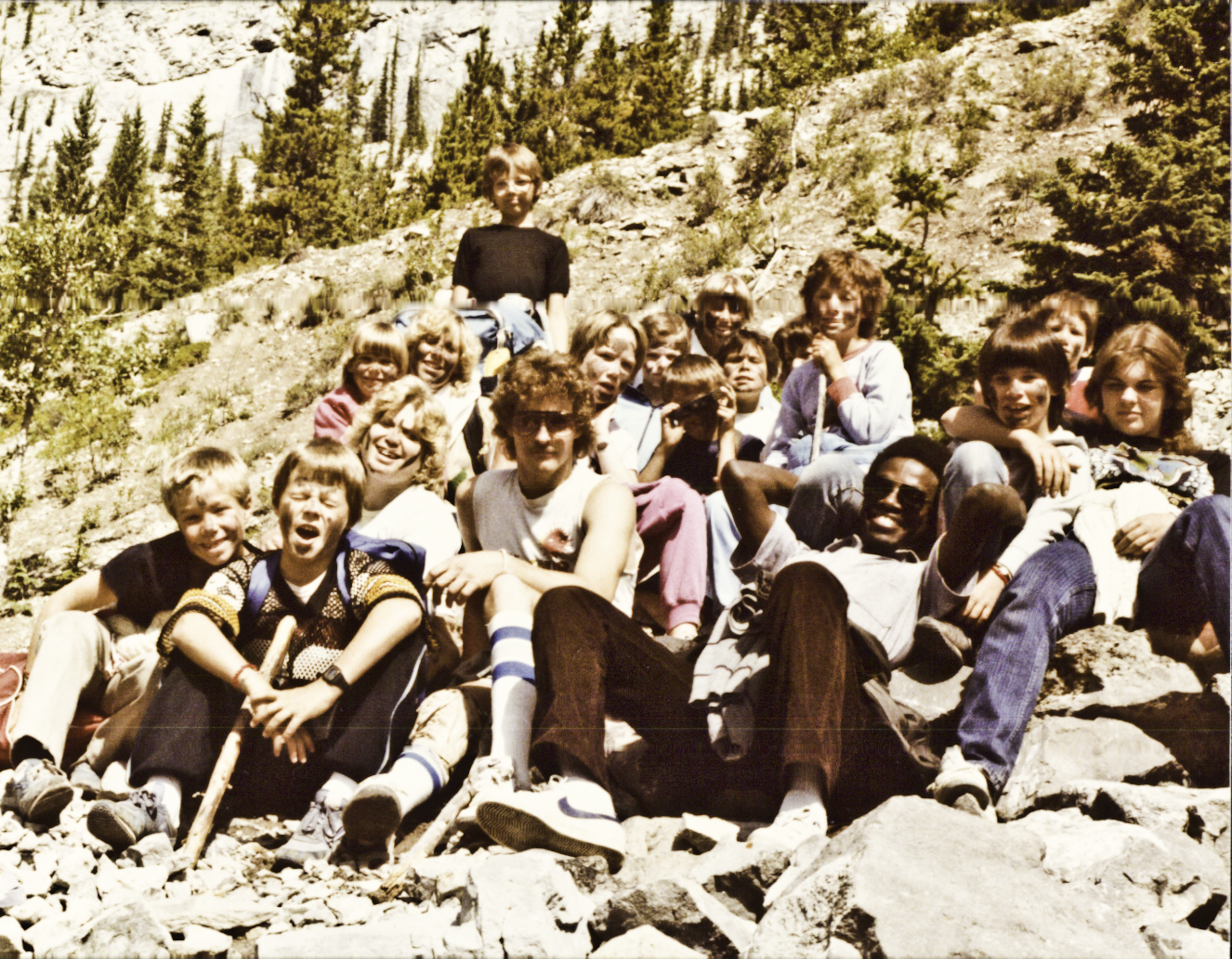

Male Grizzly Bear Camping in the Rockies, 1983

Camping in the Rockies, 1983 Panorama of Calgary and Rocky Mountains. Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Panorama of Calgary and Rocky Mountains. Calgary, Alberta, Canada Compact Disc

Compact Disc Alberta Children's Hospital 1985 Standing L-R: Dr. Michael Gayle (Jamaica), Dr. Peter Nieman (South Africa), Dr. Michael Giuffre (Canada), Dr. N. Kelly (Northern Ireland), Dr. Diane Morrison (Canada), Dr. Robert H.A. Haslam (Canada), Dr. XX, Dr. Geoffrey Mukwaya (Uganda), Dr. XY. Squatting L-R: Dr. Muniini K. Mulera (Uganda), Dr. Manjit Walia (Kenya.)

Alberta Children's Hospital 1985 Standing L-R: Dr. Michael Gayle (Jamaica), Dr. Peter Nieman (South Africa), Dr. Michael Giuffre (Canada), Dr. N. Kelly (Northern Ireland), Dr. Diane Morrison (Canada), Dr. Robert H.A. Haslam (Canada), Dr. XX, Dr. Geoffrey Mukwaya (Uganda), Dr. XY. Squatting L-R: Dr. Muniini K. Mulera (Uganda), Dr. Manjit Walia (Kenya.)