********************************************************************************************************

If you do not tell your story, someone will. If you have participated in a process, write your witness account, or else you may be erased from the story. It has happened to people that played significant roles in the struggles against Uganda’s successive dictatorships.

A person with a passion for Uganda’s history and politics is spoiled for choice among numerous scholarly books on Uganda’s political history. A sample of my favourites from our family library includes books by Abdu B. K. Kasozi, Samwiri Rubaraza Karugire, Phares Mutibwa, Dani Wadada Nabudere, George W. Kanyeihamba, David Apter, Jonathon L. Earle, I. R. Hancock, A. F. Robertson, D. Anthony Low, Audrey Richards, Holger B. Hansen, and Alicia C. Decker.

On the other hand, Uganda has an alarmingly low number of autobiographies - call them memoirs if you will - of men and women who actively shaped the journey of our country. Most of the key political and military players of the 1950s and 1960s took their knowledge to their graves. If they left manuscripts, journals, or other personal papers, they are gathering dust and mold in their private residences.

We do not blame those who died prematurely due to illness or at the hands of violent captors of the state. However, we lament the failure to write memoirs by people like Milton Apolo Obote, Idi Amin Dada, Yusufu Lule, Godfrey Lukongwa Binaisa, John Babiha, William Wycliff Rwetsiba, Abu Kakyama Mayanja, Cuthbert Obwangor, Grace Katebarirwe Ibingira, Emmanuel B. S. Lumu, Matiya Ngobi, Balaki Kebba Kirya, George B. Magezi, Felix Kenyi Onama, Sam Ngude Odaka, Eli Nasani Bisamunyu, John Bikangaga, John W. Lwamafa, Kosiya Kikira, Kamu Karekaho Karegyesa, and Aggrey Siryoyi Awori. They denied us a wealth of information that we would have sieved through to get a composite story of “how they saw it.”

It is our good fortune that Sir Edward Mutesa II left us a personal account of his life, his kingdom, and the country he led as our first president for two-and-a-half years. Desecration of My Kingdom (Constable, 1967) is an indispensable document for anyone that is interested in the Ugandan story. In my view, it should be required reading and discussion by senior four students.

We are also fortunate to have recent autobiographies by active participants in our story like Rhoda Kalema and Sarah Ntiro which are must-reads for those who want to learn and be inspired by two of our finest women leaders that successfully stood shoulder-to-shoulder with men in a male dominated political environment.

For obvious reasons, Uganda’s political history in the last forty-five years is of special interest to me. While today’s political condition in Uganda is a product of more than a century of events, the post-Amin period has been characterised by sustained drama, struggles for personal power and control of wealth, and, for many, great disappointment over what could have been.

I have been privileged to read autobiographies by many people who have been frontline participants in Uganda’s politics in the last four decades. Naturally, they are all worth the investment in time, for I have learnt something unique from each of them. However, there are five that I have read twice because I have found them to be very enlightening and, would gladly recommend them to anyone who wants to understand post-Amin politics, and the Museveni era.

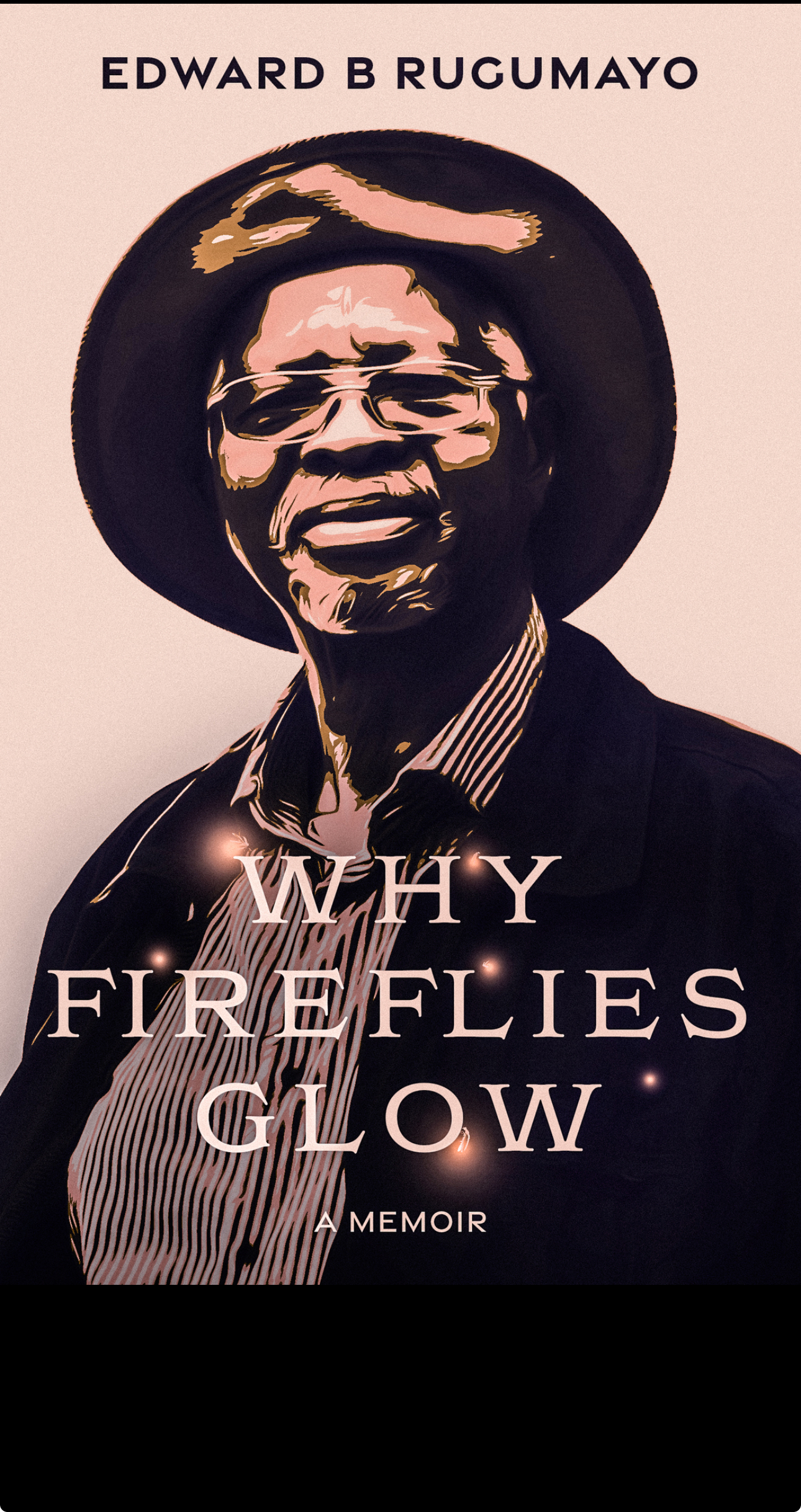

The five, in order of year of publication, are Sowing the Mustard Seed by Yoweri Kaguta Museveni (1997), The Betrayal by Samuel Kalega Njuba (2013), The Bell Is Ringing by Martin Aliker (2018), 70 Years a Witness by Matthew Rukikaire, (2019), and Why Fireflies Glow by Edward Bitanywaine Rugumayo (2023).

The importance of Museveni’s book is obvious. The author is a man who has shaped and dominated Uganda’s political journey since he led a group of, mostly, young people to war in 1981. His version of the story and self-evaluation are essential to understanding him. Whether one agrees or disagrees with Museveni, his book is worth reading to determine to what extent he has lived up to his promises.

Njuba’s book is a brutally frank statement of disappointment by a man who took risks for the cause that brought Museveni to power. Obviously, one must interrogate some of his allegations through careful inquiry, but there are publicly known events about which he expounds in a gripping, and sobering manner.

Aliker’s book is particularly fascinating because it is written by a man who was on the ringside before independence and sat in the cabinet towards the end of his political career. It should also inspire anyone who wishes to plot a path to success using clarity of purpose, honest means, hard work, and patience. For me, it is his take on the Museveni government in which he served that I consider the highlight of his outstanding book.

Rukikaire’s book enjoys a special place on my bookshelf. It is among those that I will read at least one more time. His treatment of his ancestral origins, his childhood, his early education, and Uganda’s early politics before the military coup of 1971 cover a period that captivates my interest. However, it is his risky role as host of the fighting force that started the civil war in 1981 that makes his account of the post-Amin, post-Luwero story very compelling. It is also his self-evident concern about the rulers’ departure from the original ideals of the National Resistance Movement (NRM) that makes his book a must-read by Ugandans, especially members of the NRM to which Rukikaire still belongs.

Rugumayo’s book tells the story from inside the government of Idi Amin, then the politics of Ugandans in exile, and the machinations that brought us presidents Yusufu Lule, Binaisa, Obote, and Museveni. His insider’s account of the plots and counterplots by the self-styled liberators that followed the fall of Amin is, to me, the most credible account I have read on that period. He kept contemporaneous notes that enabled him to recall details with evident confidence. He reveals shocking details about plots to kill him and other political players in that chaotic period. A masterpiece of writing, and a confirmation that politics of treachery replaced politics of treachery. The wheels are still spinning in place.

Great books all of them. Worth reading. Worth reflection. One waits to read more from others that have contributed to our collective story.

© Muniini K. Mulera